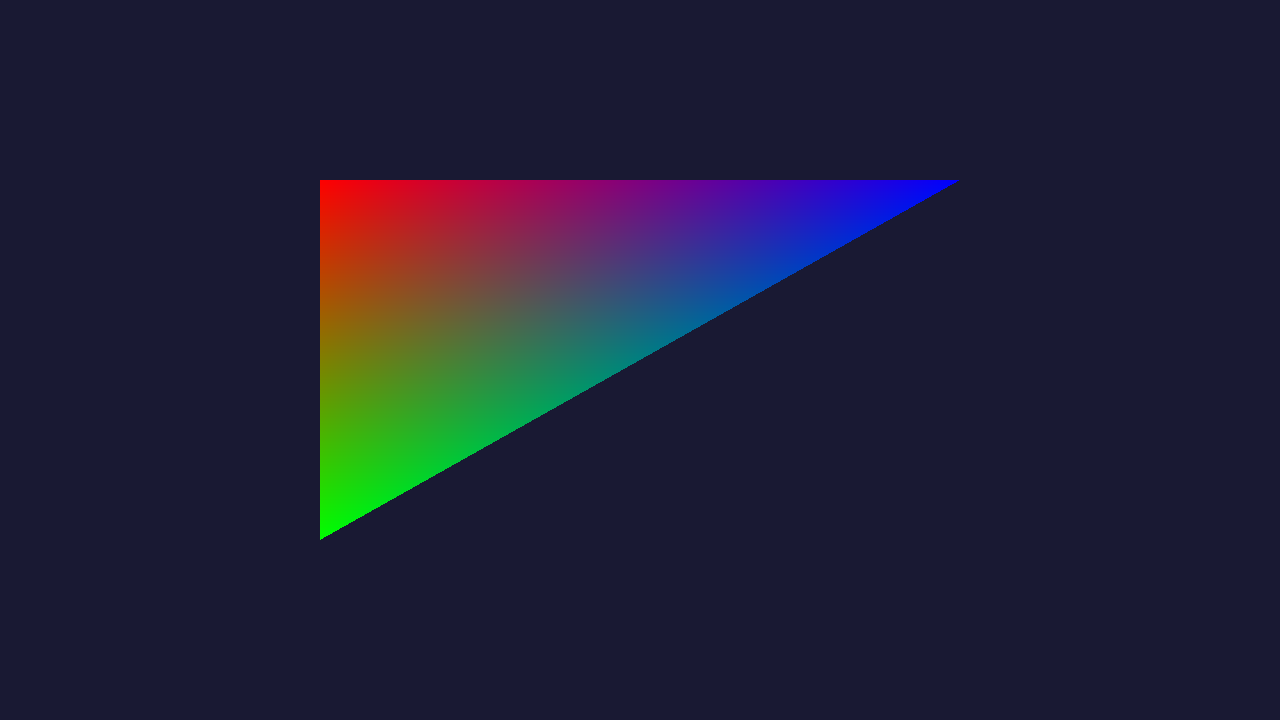

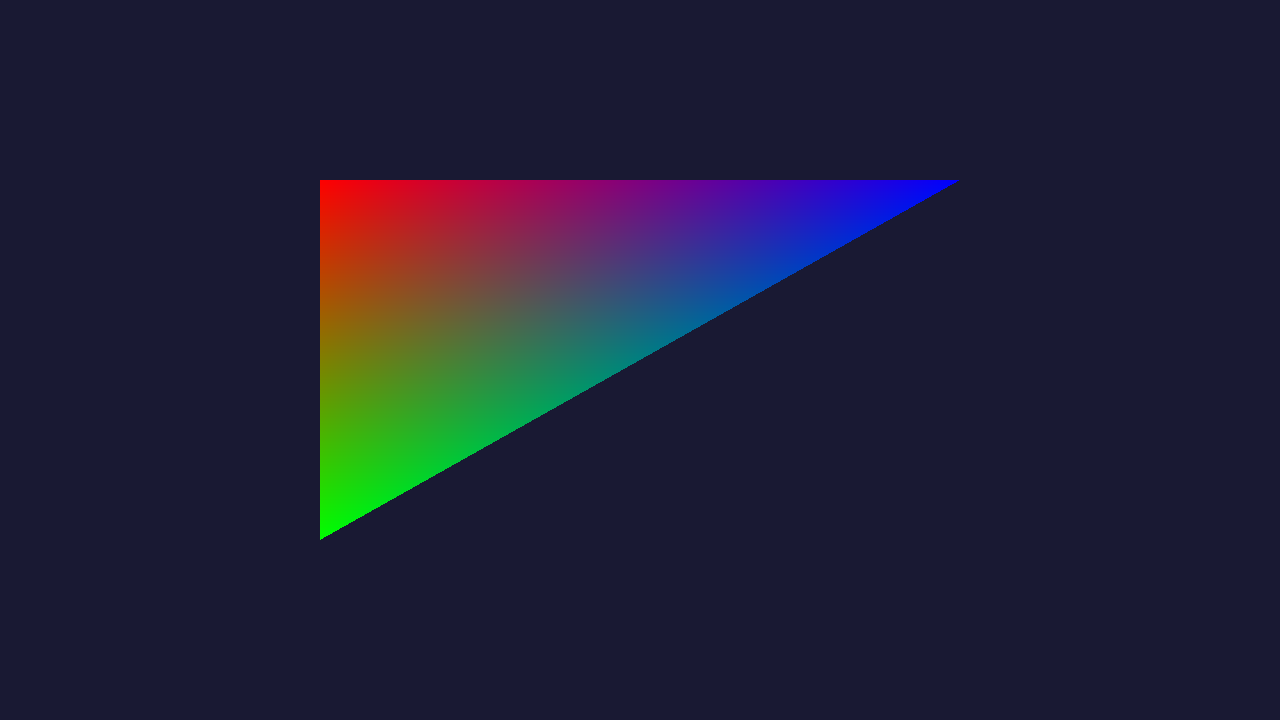

Introduction to "Hello Triangle", the most basic Vulkan application.

Our first triangle!

- Note

- The source for this sample can be found in samples/hellotriangle in the SDK.

Introduction

In this sample, we will draw our first triangle to the screen. There are a lot of concepts to internalize for this sample.

Structure of Samples

All samples implement a global function which creates the application. This is so we can move the main loop outside every sample.

VulkanApplication *MaliSDK::createApplication()

{

return new HelloTriangle();

}

Initialization

The samples are initialized first once in VulkanApplication::initialize, then later the application will be called in updateSwapchain() every time the swapchain is invalidated or otherwise changes. Most initialization happens in updateSwapchain() since many of our resources will in some way depend on the swapchain.

We start off by creating a vertex buffer for our triangle, as well as creating a pipeline cache. The pipeline cache allows us to cache previously compiled pipelines and shaders if they are built multiple times. For this particular sample, it is strictly not necessary, but it is very useful to know about.

bool HelloTriangle::initialize(Context *pContext)

{

this->pContext = pContext;

initVertexBuffer();

VkPipelineCacheCreateInfo pipelineCacheInfo = { VK_STRUCTURE_TYPE_PIPELINE_CACHE_CREATE_INFO };

VK_CHECK(vkCreatePipelineCache(pContext->getDevice(), &pipelineCacheInfo, nullptr, &pipelineCache));

return true;

}

Top-left Always

Vulkan's coordinate system is always top-left. This means that (X = -1, Y = -1) in normalized device coordinates will be top-left. This is opposite of OpenGL and OpenGL ES which is bottom-left.

static const Vertex data[] = {

{

vec4(-0.5f, -0.5f, 0.0f, 1.0f), vec4(1.0f, 0.0f, 0.0f, 1.0f),

},

{

vec4(-0.5f, +0.5f, 0.0f, 1.0f), vec4(0.0f, 1.0f, 0.0f, 1.0f),

},

{

vec4(+0.5f, -0.5f, 0.0f, 1.0f), vec4(0.0f, 0.0f, 1.0f, 1.0f),

},

};

vertexBuffer = createBuffer(data, sizeof(data), VK_BUFFER_USAGE_VERTEX_BUFFER_BIT);

- Note

- This triangle will have two vertices towards the top of the screen. It is still a counter-clockwise triangle, since the Vulkan specification negates the sign in its area computation when calculating the winding order.

Creating a Buffer

In order to create a buffer, we need to specify our usage as well as size.

Buffer buffer;

VkDevice device = pContext->getDevice();

VkBufferCreateInfo info = { VK_STRUCTURE_TYPE_BUFFER_CREATE_INFO };

info.usage = usage;

info.size = size;

VK_CHECK(vkCreateBuffer(device, &info, nullptr, &buffer.buffer));

After creating a buffer, we have not allocated memory for it yet. To do this, we will need to query the requirements for the buffer.

The requirements of a buffer specify how much memory is required, alignment (needed if we place many buffers in a larger allocation), and which memory types can support this buffer.

A Vulkan device will support one or more memory types depending on the implementation. Integrated GPUs such as Mali will typically support one or two memory types, which typically distinguishes between cached memory or not.

Devices with ARM GPUs have a unified memory architecture such that both the CPU and GPU can access the same physical memory if the memory manager has been configured the right way.

VkMemoryRequirements memReqs;

vkGetBufferMemoryRequirements(device, buffer.buffer, &memReqs);

VkMemoryAllocateInfo alloc = { VK_STRUCTURE_TYPE_MEMORY_ALLOCATE_INFO };

alloc.allocationSize = memReqs.size;

alloc.memoryTypeIndex = findMemoryTypeFromRequirements(

memReqs.memoryTypeBits, VK_MEMORY_PROPERTY_HOST_VISIBLE_BIT | VK_MEMORY_PROPERTY_HOST_COHERENT_BIT);

VK_CHECK(vkAllocateMemory(device, &alloc, nullptr, &buffer.memory));

vkBindBufferMemory(device, buffer.buffer, buffer.memory, 0);

Based on memReqs.memoryTypeBits, we get a bitmask which specifies which memory types this buffer can be backed by. These memory types might have different characteristics, so we need to match the available memory types with something that we can use, for example here, we need the buffer to be HOST_VISIBLE.

uint32_t HelloTriangle::findMemoryTypeFromRequirements(uint32_t deviceRequirements, uint32_t hostRequirements)

{

const VkPhysicalDeviceMemoryProperties &props = pContext->getPlatform().getMemoryProperties();

for (uint32_t i = 0; i < VK_MAX_MEMORY_TYPES; i++)

{

if (deviceRequirements & (1u << i))

{

if ((props.memoryTypes[i].propertyFlags & hostRequirements) == hostRequirements)

{

return i;

}

}

}

LOGE("Failed to obtain suitable memory type.\n");

abort();

}

To "upload" our data to the buffer, we can simply map it, and copy. There is no requirement in Vulkan that we unmap the buffer before using it, but we will not modify this buffer any more, so unmapping makes sense.

if (pInitialData)

{

void *pData;

VK_CHECK(vkMapMemory(device, buffer.memory, 0, size, 0, &pData));

memcpy(pData, pInitialData, size);

vkUnmapMemory(device, buffer.memory);

}

Creating the Renderpass

In Vulkan, we need to specify a render pass up front. Which attachments will we use, are we going to clear the render target on start? Will we preserve any attachments? All these decisions are crucial for a tile based architecture such as Mali.

For this sample, we only have a single color buffer which we render a triangle to. First, we specify our attachment.

VkAttachmentDescription attachment = { 0 };

attachment.format = format;

attachment.samples = VK_SAMPLE_COUNT_1_BIT;

attachment.loadOp = VK_ATTACHMENT_LOAD_OP_CLEAR;

attachment.storeOp = VK_ATTACHMENT_STORE_OP_STORE;

attachment.stencilLoadOp = VK_ATTACHMENT_LOAD_OP_DONT_CARE;

attachment.stencilStoreOp = VK_ATTACHMENT_STORE_OP_DONT_CARE;

attachment.initialLayout = VK_IMAGE_LAYOUT_UNDEFINED;

attachment.finalLayout = VK_IMAGE_LAYOUT_PRESENT_SRC_KHR;

Creating the Subpass

Inside a renderpass, there can be multiple subpasses. For now, we can make it simple and just assume a single subpass. In the subpass we specify that we have a single color attachment.

VkAttachmentReference colorRef = { 0, VK_IMAGE_LAYOUT_COLOR_ATTACHMENT_OPTIMAL };

VkSubpassDescription subpass = { 0 };

subpass.pipelineBindPoint = VK_PIPELINE_BIND_POINT_GRAPHICS;

subpass.colorAttachmentCount = 1;

subpass.pColorAttachments = &colorRef;

VkRenderPassCreateInfo rpInfo = { VK_STRUCTURE_TYPE_RENDER_PASS_CREATE_INFO };

rpInfo.attachmentCount = 1;

rpInfo.pAttachments = &attachment;

rpInfo.dependencyCount = 1;

rpInfo.pDependencies = &dependency;

rpInfo.subpassCount = 1;

rpInfo.pSubpasses = &subpass;

VK_CHECK(vkCreateRenderPass(pContext->getDevice(), &rpInfo, nullptr, &renderPass));

Image Layout Transitions

Before we start rendering, we need to make an image layout transition. This is a completely new concept in Vulkan if you are used to older graphics APIs. The purpose of an image layout is to allow the GPU to better optimize based on how an image is being accessed. VK_IMAGE_LAYOUT_GENERAL is a generic layout that will work in all cases, but could be suboptimal on certain GPUs.

- Note

- For Mali GPUs in particular, VK_IMAGE_LAYOUT_GENERAL is just as good as any "optimal" layout, but in this sample, we try to take the "correct" route, which should be optimal on any GPU that supports Vulkan. Even if we were to always go with IMAGE_LAYOUT_GENERAL, we still need to make layout transitions into PRESENT_SRC_KHR for images which are part of the swapchain, so it's not something we can entirely ignore.

We make use of render pass attachments to do our layout transition. We want to transition into the COLOR_ATTACHMENT_OUTPUT_BIT. At the start of the frame, we will clear the image, so we do not care about preserving any of the image. In this case we can transition from an "undefined" layout, which effectively invalidates any data found in the render target.

In our render pass, we can describe how image layouts will change over time. We need to describe the initial state of a render target attachment:

attachment.initialLayout = VK_IMAGE_LAYOUT_UNDEFINED;

The application must ensure that the layout used here is accurate. Vulkan will not transition anything into the initialLayout for you. The special case here is UNDEFINED layout, since it effectively means you don't care about the layout.

When a subpass begins, images are transitioned into an image layout. This image layout depends on the VkAttachmentReference. In our case, we want COLOR_ATTACHMENT_OPTIMAL.

VkAttachmentReference colorRef = { 0, VK_IMAGE_LAYOUT_COLOR_ATTACHMENT_OPTIMAL };

After all subpasses are complete, there is a final transition to the finalLayout.

attachment.finalLayout = VK_IMAGE_LAYOUT_PRESENT_SRC_KHR;

This creates the desired effect that we invalidate, transition to ATTACHMENT_OPTIMAL while we render, then finally transition to PRESENT_SRC_KHR. This image can now be presented.

Adding Subpass Dependency

The image layout transition as part of a subpass will happen without any waiting. This is bad because the presentation engine can still be reading from the image. To properly enforce this we need to add an external dependency to our first subpass where the layout transition happens.

VkSubpassDependency dependency = { 0 };

dependency.srcSubpass = VK_SUBPASS_EXTERNAL;

dependency.dstSubpass = 0;

dependency.srcStageMask = VK_PIPELINE_STAGE_COLOR_ATTACHMENT_OUTPUT_BIT;

dependency.dstStageMask = VK_PIPELINE_STAGE_COLOR_ATTACHMENT_OUTPUT_BIT;

dependency.srcAccessMask = 0;

dependency.dstAccessMask = 0;

As source subpass we use EXTERNAL, which means that we wait for something outside the renderpass itself to complete before we begin the first subpass. An important point here is that we use COLOR_ATTACHMENT_OUTPUT_BIT as our StageMask. When we later submit our command buffer we will only let a certain pipeline stage wait for our semaphore. By having our subpass dependency wait for that stage we create a dependency chain which ensures that the layout transition happens after the semaphore signals.

const VkPipelineStageFlags waitStage = VK_PIPELINE_STAGE_COLOR_ATTACHMENT_OUTPUT_BIT;

info.waitSemaphoreCount = acquireSemaphore != VK_NULL_HANDLE ? 1 : 0;

info.pWaitSemaphores = &acquireSemaphore;

info.pWaitDstStageMask = &waitStage;

Only the fragment parts of the graphics pipeline needs to wait. Vertex can run completely in parallel.

Creating the Pipeline

In Vulkan, a lot of state which affects rendering is bundled together into a large blob called the VkPipeline. The pipeline specifies which shaders to use, blend state, depth stencil state, and much more. It is a huge block of state.

typedef struct VkGraphicsPipelineCreateInfo {

VkStructureType sType;

const void* pNext;

VkPipelineCreateFlags flags;

uint32_t stageCount;

const VkPipelineShaderStageCreateInfo* pStages;

const VkPipelineVertexInputStateCreateInfo* pVertexInputState;

const VkPipelineInputAssemblyStateCreateInfo* pInputAssemblyState;

const VkPipelineTessellationStateCreateInfo* pTessellationState;

const VkPipelineViewportStateCreateInfo* pViewportState;

const VkPipelineRasterizationStateCreateInfo* pRasterizationState;

const VkPipelineMultisampleStateCreateInfo* pMultisampleState;

const VkPipelineDepthStencilStateCreateInfo* pDepthStencilState;

const VkPipelineColorBlendStateCreateInfo* pColorBlendState;

const VkPipelineDynamicStateCreateInfo* pDynamicState;

VkPipelineLayout layout;

VkRenderPass renderPass;

uint32_t subpass;

VkPipeline basePipelineHandle;

int32_t basePipelineIndex;

} VkGraphicsPipelineCreateInfo;

The advantage of doing this is that the driver has full knowledge up front how rendering will happen. Also, when we later want to use the pipeline, we can bind it all in one go to a command buffer instead of making many separate calls.

The pipeline setup here is not very exciting. The main thing we need to set up is our vertex input structure. We have a vertex buffer with interleaved position and color data, which needs to be specified.

VkVertexInputAttributeDescription attributes[2] = { { 0 } };

attributes[0].location = 0;

attributes[0].binding = 0;

attributes[0].format = VK_FORMAT_R32G32B32A32_SFLOAT;

attributes[0].offset = 0;

attributes[1].location = 1;

attributes[1].binding = 0;

attributes[1].format = VK_FORMAT_R32G32B32A32_SFLOAT;

attributes[1].offset = 4 * sizeof(float);

VkVertexInputBindingDescription binding = { 0 };

binding.binding = 0;

binding.stride = sizeof(Vertex);

binding.inputRate = VK_VERTEX_INPUT_RATE_VERTEX;

Using SPIR-V Shaders

VkPipelineShaderStageCreateInfo shaderStages[2] = {

{ VK_STRUCTURE_TYPE_PIPELINE_SHADER_STAGE_CREATE_INFO },

{ VK_STRUCTURE_TYPE_PIPELINE_SHADER_STAGE_CREATE_INFO },

};

shaderStages[0].stage = VK_SHADER_STAGE_VERTEX_BIT;

shaderStages[0].module = loadShaderModule(device, "shaders/triangle.vert.spv");

shaderStages[0].pName = "main";

shaderStages[1].stage = VK_SHADER_STAGE_FRAGMENT_BIT;

shaderStages[1].module = loadShaderModule(device, "shaders/triangle.frag.spv");

shaderStages[1].pName = "main";

VkGraphicsPipelineCreateInfo pipe = { VK_STRUCTURE_TYPE_GRAPHICS_PIPELINE_CREATE_INFO };

pipe.stageCount = 2;

pipe.pStages = shaderStages;

...

VkShaderModule loadShaderModule(VkDevice device, const char *pPath)

{

vector<uint32_t> buffer;

if (FAILED(OS::getAssetManager().readBinaryFile(&buffer, pPath)))

{

LOGE("Failed to read SPIR-V file: %s.\n", pPath);

return VK_NULL_HANDLE;

}

VkShaderModuleCreateInfo moduleInfo = { VK_STRUCTURE_TYPE_SHADER_MODULE_CREATE_INFO };

moduleInfo.codeSize = buffer.size() * sizeof(uint32_t);

moduleInfo.pCode = buffer.data();

VkShaderModule shaderModule;

VK_CHECK(vkCreateShaderModule(device, &moduleInfo, nullptr, &shaderModule));

return shaderModule;

}

The SPIR-V binary shaders have been built in the build system via CMake.

Building VkImageView and VkFramebuffer for Swapchain Images

In the updateSwapchain callback, we know which swapchain images we will render the triangles to. We create the required number of VkImageViews and VkFramebuffers.

In Vulkan, when images are used for rendering or sampling, we need to create an "image view". The image view describes how we will interpret the image we create the view from. We might have a mipmapped texture where we create a single mip-level image, or we can reinterpret the format. In this scenario however, we will simply create an "identity" view.

When creating a framebuffer, we give it the attachments we will use, and these attachments must be VkImageViews. We need to create separate image views and framebuffers for each swapchain image that is in use, since we can be asked to render into any of the swapchain images.

for (auto image : newBackbuffers)

{

VkImageViewCreateInfo view = { VK_STRUCTURE_TYPE_IMAGE_VIEW_CREATE_INFO };

view.viewType = VK_IMAGE_VIEW_TYPE_2D;

view.format = dim.format;

view.image = image;

view.subresourceRange.baseMipLevel = 0;

view.subresourceRange.baseArrayLayer = 0;

view.subresourceRange.levelCount = 1;

view.subresourceRange.layerCount = 1;

view.subresourceRange.aspectMask = VK_IMAGE_ASPECT_COLOR_BIT;

view.components.r = VK_COMPONENT_SWIZZLE_R;

view.components.g = VK_COMPONENT_SWIZZLE_G;

view.components.b = VK_COMPONENT_SWIZZLE_B;

view.components.a = VK_COMPONENT_SWIZZLE_A;

VK_CHECK(vkCreateImageView(device, &view, nullptr, &backbuffer.view));

VkFramebufferCreateInfo fbInfo = { VK_STRUCTURE_TYPE_FRAMEBUFFER_CREATE_INFO };

fbInfo.renderPass = renderPass;

fbInfo.attachmentCount = 1;

fbInfo.pAttachments = &backbuffer.view;

fbInfo.width = width;

fbInfo.height = height;

fbInfo.layers = 1;

VK_CHECK(vkCreateFramebuffer(device, &fbInfo, nullptr, &backbuffer.framebuffer));

backbuffers.push_back(backbuffer);

}

Rendering a Frame

Finally, we can start rendering to the screen. First of all, we need a command buffer which we can record into.

Requesting Command Buffer

VkCommandBuffer cmd = pContext->requestPrimaryCommandBuffer();

The command buffer is allocated from a VkCommandPool which is tied to the swapchainIndex.

VkCommandBuffer Context::requestPrimaryCommandBuffer()

{

return perFrame[swapchainIndex]->commandManager.requestCommandBuffer();

}

VkCommandBuffer CommandBufferManager::requestCommandBuffer()

{

VkCommandBuffer ret = VK_NULL_HANDLE;

if (count < buffers.size())

{

ret = buffers[count++];

VK_CHECK(vkResetCommandBuffer(ret, VK_COMMAND_BUFFER_RESET_RELEASE_RESOURCES_BIT));

}

else

{

VkCommandBufferAllocateInfo info = { VK_STRUCTURE_TYPE_COMMAND_BUFFER_ALLOCATE_INFO };

info.commandPool = pool;

info.level = commandBufferLevel;

info.commandBufferCount = 1;

VK_CHECK(vkAllocateCommandBuffers(device, &info, &ret));

buffers.push_back(ret);

count++;

}

return ret;

}

Asynchronous GPU

It is crucial that we have some system in place for allocating command buffers. In Vulkan, submissions to the GPU are asynchronous. This means that when we submit a command buffer to the GPU, we cannot reuse it or touch it until we are certain the GPU has completed the work. While the GPU is working with a command buffer, we need to start queueing up work to a different command buffer. The next frame we will observe a different swapchainIndex, so we will allocate a command buffer from a different pool, which avoids all hazards like these.

We begin the command buffer and specify that we only intend to submit it once. This allows the driver to make certain optimizations based on this knowledge since the command buffer can potentially be scribbled on in-place without having to worry about maintaining a clean copy of the command buffer.

Beginning the Renderpass

To begin a renderpass, we need to specify the clear color values, the framebuffer we render into, the render pass and the extents of our rendering.

VkClearValue clearValue;

clearValue.color.float32[0] = 0.1f;

clearValue.color.float32[1] = 0.1f;

clearValue.color.float32[2] = 0.2f;

clearValue.color.float32[3] = 1.0f;

VkRenderPassBeginInfo rpBegin = { VK_STRUCTURE_TYPE_RENDER_PASS_BEGIN_INFO };

rpBegin.renderPass = renderPass;

rpBegin.framebuffer = backbuffer.framebuffer;

rpBegin.renderArea.extent.width = width;

rpBegin.renderArea.extent.height = height;

rpBegin.clearValueCount = 1;

rpBegin.pClearValues = &clearValue;

vkCmdBeginRenderPass(cmd, &rpBegin, VK_SUBPASS_CONTENTS_INLINE);

The actual render pass is fairly simple. First, we bind a pipeline to the command buffer.

vkCmdBindPipeline(cmd, VK_PIPELINE_BIND_POINT_GRAPHICS, pipeline);

We then specify dynamic state such as the viewport and scissor box. Here, we just use the full framebuffer size.

VkViewport vp = { 0 };

vp.x = 0.0f;

vp.y = 0.0f;

vp.width = float(width);

vp.height = float(height);

vp.minDepth = 0.0f;

vp.maxDepth = 1.0f;

vkCmdSetViewport(cmd, 0, 1, &vp);

VkRect2D scissor;

memset(&scissor, 0, sizeof(scissor));

scissor.extent.width = width;

scissor.extent.height = height;

vkCmdSetScissor(cmd, 0, 1, &scissor);

- Note

- It is possible to bake the viewport and scissor state into the VkPipeline itself, but in this sample, we explicitly defined that VIEWPORT and SCISSOR state should be dynamic and modifyable outside the pipeline.

We can now bind our vertex buffer, draw the triangle, and finally, end the render pass.

VkDeviceSize offset = 0;

vkCmdBindVertexBuffers(cmd, 0, 1, &vertexBuffer.buffer, &offset);

vkCmdDraw(cmd, 3, 1, 0, 0);

vkCmdEndRenderPass(cmd);

We can now end our command buffer and submit it to the device.

VK_CHECK(vkEndCommandBuffer(cmd));

pContext->submitSwapchain(cmd);

When we submit a command buffer which interacts with the swapchain, we need to make sure of Vulkan semaphores. When we acquired the swapchain image, we provided an acquireSemaphore which will be signalled later on the GPU when it becomes safe to render into the image.

When submitting a command buffer, we also specify that we need to wait for a semaphore first. We can also specify that only the COLOR_ATTACHMENT_OUTPUT_BIT stage actually needs to be blocked. We can still perform vertex processing or other tasks without blocking on the swapchain. This is critical for getting optimal parallelism for tiled GPUs such as Mali.

After the command buffer completes, we need to signal a release semaphore. This semaphore is then used in vkQueuePresentKHR which needs to wait for the GPU to complete rendering in order to correctly display results on screen.

void Context::submitSwapchain(VkCommandBuffer cmd)

{

submitCommandBuffer(cmd, getSwapchainAcquireSemaphore(), getSwapchainReleaseSemaphore());

}

void Context::submitCommandBuffer(VkCommandBuffer cmd, VkSemaphore acquireSemaphore, VkSemaphore releaseSemaphore)

{

VkFence fence = getFenceManager().requestClearedFence();

VkSubmitInfo info = { VK_STRUCTURE_TYPE_SUBMIT_INFO };

info.commandBufferCount = 1;

info.pCommandBuffers = &cmd;

const VkPipelineStageFlags waitStage = VK_PIPELINE_STAGE_COLOR_ATTACHMENT_OUTPUT_BIT;

info.waitSemaphoreCount = acquireSemaphore != VK_NULL_HANDLE ? 1 : 0;

info.pWaitSemaphores = &acquireSemaphore;

info.pWaitDstStageMask = &waitStage;

info.signalSemaphoreCount = releaseSemaphore != VK_NULL_HANDLE ? 1 : 0;

info.pSignalSemaphores = &releaseSemaphore;

VK_CHECK(vkQueueSubmit(queue, 1, &info, fence));

}

Using Fences to Keep Track of GPU Progress

When we submit a command buffer to the GPU, we do not wait on the CPU. In theory, we could queue up as many frames as we wish for, but this has an effect on latency and the fact that we need to keep track of a lot of command buffers. We typically only want to queue up 2-3 frames at most in order to keep both CPU and GPU busy. When GPU has enough work to do, we want to wait on the CPU until the GPU completes more work.

We implement this by keeping a list of fences which were triggered for a given swapchainIndex.

VkFence fence = getFenceManager().requestClearedFence();

FenceManager &Context::getFenceManager()

{

return perFrame[swapchainIndex]->fenceManager;

}

The next time we observe a swapchain index in AcquireNextImageKHR, we can wait for all the fences which belong to that swapchain index. This allows us to cleanly bound the latency to a fixed number of frames with optimal throughput. After acquiring a swapchain index, we wait for the fences in question in Context::beginFrame().

void Context::PerFrame::beginFrame()

{

fenceManager.beginFrame();

commandManager.beginFrame();

for (auto &pManager : secondaryCommandManagers)

pManager->beginFrame();

}

void FenceManager::beginFrame()

{

if (count != 0)

{

vkWaitForFences(device, count, fences.data(), true, UINT64_MAX);

vkResetFences(device, count, fences.data());

}

count = 0;

}