|

OpenGL ES SDK for Android

ARM Developer Center

|

|

OpenGL ES SDK for Android

ARM Developer Center

|

Illustrates the use of sync objects to synchronise the use of shared objects between multiple contexts in multiple threads.

The source for this sample can be found in the folder of the SDK.

As we move to more complex graphics applications there will be a moment when we will want to use multithreading (MT). A typical situation is when our graphics application needs to perform intensive mathematical operations. In such a case, performance may be improved by moving the intensive workload to a separate thread, different to the one devoted to managing the graphics operations. Another common case is when we want the Graphical User Interface (GUI) to run in a separate thread.

The benefits from multithreading are really important. MT allows us to keep the application process responsive and it is relevant not only in connection with the application's GUI. Any device is permanently executing a lot of extra tasks in the background especially network related services. It is then critical to perform heavy tasks in a secondary thread.

Nowadays more embedded devices come with a multi-processor architecture. If we really want to squeeze this entire horsepower then we definitely need MT. Technologies such as hyper-threading and multi-core processors can only be effectively exploited if the processors have to manage multiple concurrent threads.

The threaded programming model implicitly has the need of synchronization. Every multi-threaded application needs to manage its different threads in a coordinated way. The synchronization between threads can be performed by means of standard mutexes, semaphores and condition variables available in MT libraries.

This sample covers the scenario where all threads are devoted to graphics operations and use multiple rendering contexts and OpenGL ES 3.0 sync objects to help achieve synchronization.

Multiple rendering contexts are required when an application manages more than one rendering window and when multiple threads share OpenGL ES objects. To illustrate this latter case, let's think about a hypothetical application that renders a texture which is frequently updated. The user modifies a texture which is mapped to the face of the character. We would like to update the texture in a separate thread and synchronize this action with rendering happening on the main thread.

In the case described above when the application manages multiple contexts and multiple threads, or data are shared between OpenGL ES and other APIs such as OpenCL, it may be necessary to determine whether commands sent to the GPU have finished yet and whether the results of those commands are ready to be used. OpenGL ES includes two instructions to force the GPU to start working on commands or to finish working on commands that have been issued so far: glFlush() and glFinish(). The first ensures that all commands issued so far are at least placed into the start of the command queue and that they will eventually be executed. The second, on the other hand, actually ensures that all commands issued have been fully executed and that the command queue is empty but this can reduce performance drastically.

Commonly in applications with multiple threads and contexts, it is necessary to know whether OpenGL ES has finished executing a set of commands up to a given point, especially when contexts are sharing data. This kind of synchronization is performed by special objects known as sync objects. In OpenGL ES 2.0, synchronization objects are available only by means of extensions which are not always available on all platforms and devices. See for example KHR_fence_sync [1], ANDROID_native_fence_sync [2], and KHR_reusable_sync [3].

In OpenGL ES 3.0 sync objects are already part of the API and their use has also been simplified. The available command to create a sync object is shown below:

Synchronization objects have two possible states: signaled and unsignaled. When glFenceSync creates a sync object it is in the unsignaled state. It also inserts a fence command into the OpenGL ES command stream and associates it with the sync object. This state changes to signaled when the condition of the glFenceSync command is satisfied, i.e. all commands in the command stream up to the point of the fence are complete. According to Khronos' specification, "all effects from these commands on GL client and server state and the frame buffer are fully realized".

To cause OpenGL ES to wait for the sync object to become signaled, there are two functions that we can use:

and

The function glClientWaitSync blocks all CPU operations until a sync object is signaled. If the sync object does not become signaled within the timeout time, the function returns a status code to indicate so.

For glWaitSync, the behaviour is slightly different. Graphics commands are performed on the GPU in strict order, so when a sync object is reached in the command stream, it is guaranteed that all preceding commands have been completed.

The application won't actually wait for the sync object to become signaled; only the GPU will. Therefore, glWaitSync will return to the application immediately. Because the application does not wait for the function to return, there is no danger of hanging, and so the flags value must be set to zero. Also, the timeout will actually be implementation dependent and so the special timeout value GL_TIMEOUT_IGNORED is specified to make this clear. The timeout value used by your implementation can be retrieved by calling glGet with the parameter GL_MAX_SERVER_WAIT_TIMEOUT.

If the fence command associated with a given sync object has completed, or if no glWaitSync or glClientWaitSync commands are blocking on sync, the object is deleted immediately. Otherwise, the sync object is flagged for deletion. To delete a fence object we have created the below command is used:

After glDeleteSync returns, the name sync is invalid and can no longer be used to refer to the sync object.

Finally there is a command to query the properties of a sync object:

On success, glGetSynciv replaces up to bufSize integers in values with the corresponding property values of the object being queried (GL_OBJECT_TYPE, GL_SYNC_STATUS and GL_SYNC_CONDITION).

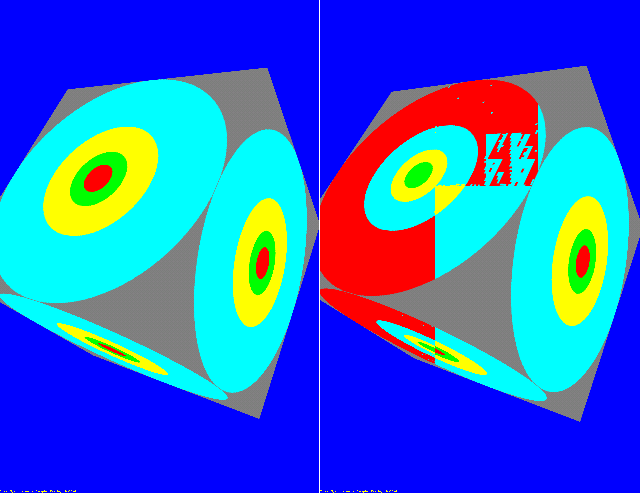

The application in our example manages two threads. The main thread is responsible for rendering a spinning cube with a texture of circles with different colours. A second thread is devoted to modifying (by animating the colours) and uploading the texture. If no fence is implemented, we would expect some kind of artefacts when the rendering is taking place at the same time the texture is being updated. To avoid this undesirable effect, two fence objects are implemented. A simple touch on the screen will switch on/off the use of the fence objects.

A simplified version of the rendering function is shown below:

The instruction glWaitSync at the beginning of the render function will make the GPU wait for the sync object sndThreadSyncObj, which is signalled when the texture upload is complete. In the simplified code below, you can see the secondary thread's call to glFenceSync. This command creates the sndThreadSyncObj sync object after the texture has been uploaded with glTexImage2D. The sync object sndThreadSyncObj is signalled when the GPU reaches the equivalent fence sync command in the command stream. Only then will the graphics commands sent to the GPU in the function renderFrame be executed. In this way, we guarantee that the cube will be rendered only once the texture update has finished.

We must also prevent any texture changes while the frame is being rendered. This is the reason we use a second sync object called mainThreadSyncObj. This is created at the end of the renderFrame function and is used before the texture update in the secondary thread to make sure that we do not start updating the texture while the frame is being rendered.

As you can see, by means of sync objects we can synchronize GPU actions in a very similar way to how mutual exclusives are used to synchronize behaviour between threads.

The use of fencing is on by default when the application starts. Every time the user touches the screen the use of fencing is toggled on and off. The current state of fencing is displayed at the bottom of the screen. The image below shows the effect of turning fencing on and off on a Nexus 10. As you can see, artifacts can be caused when the threads are not synchronized.

Working in OpenGL ES within a multi-threaded environment requires some minor additional work in your application. In order to work with multiple threads in OpenGL ES, we must follow these rules:

In the case of multiple threads sharing a single rendering context, we must unbind the context from the thread where it is current before making it current to any other thread. The order of operations is as follows:

This sample focuses on a different situation; each thread has its own rendering context and as the contexts are different both can be current at the same time. Creating a separate rendering context per thread has clear advantages. Firstly, we do not need to worry about unbinding and binding from one thread to another the only existing rendering context which is a common cause of application hanging. Secondly, which is more important we do not harm the performance as we can keep the command queue fed uninterruptedly. Every time the rendering context is unbound from a thread this thread can't perform any graphics operation. This kind of context switching can degrade the application performance especially if it takes place very frequently.

In our main application thread, the rendering context is created and initialized in the MaliSamplesView class in MaliSamplesView.java file. We are using the OpenGL ES APIs provided by the Android framework.

A second thread is created during the main thread graphics set up by calling the function createTextureThread(). At the beginning of the new thread's working function a new pixel buffer surface and rendering context are created as shown below.

In the secondary thread we do not perform any drawing operation on a window surface so we create a small off-screen pixel buffer surface. If you are working with an off-screen surface you can experience problems in creating it. In this case the recommended procedure is to start from a minimal set of attributes, for example indicating only the width and height, and once you get a valid surface you can try to add more attributes. During this procedure it is better to try first with values that are power of 2 as according to the OpenGL ES 3.0 specification "if the underlying OpenGL ES implementation does not support non-power-of-two textures, both the width and height will be a power of 2". In our case the ARM Mali-T600 Series of GPUs supports non-power-of-two values of PBuffer's width and height.

Once a valid surface is created the next step is to create the rendering context.

The third parameter passed to eglCreateContext is the rendering context of the main thread. It means that the rendering context of the secondary thread will share OpenGL ES objects with the rendering context of the main thread. In our application, both threads are sharing the texture object.

OpenGL ES rendering commands are assumed to be asynchronous. If any drawing operation is invoked there is not any guarantee that the rendering has finished by the time the call returns. Very often there is a need of synchronizing CPU-GPU or GPU-GPU actions in a MT environment. OpenGL ES provides an explicit synchronization mechanism with the glFinish() and glFlush() commands. However, these should be used with care as they can hurt performance. Some other functions implicitly force synchronization. Nevertheless, in some cases, and especially in the MT environment, there is a need to perform the kind of synchronization that OpenGL ES itself does implicitly, i.e. to sync to a specific point in the command stream. This is the purpose of the fence objects which are explained in this tutorial. Additionally the sample illustrates how to work with multiple contexts in a MT application.

[1] http://www.khronos.org/registry/vg/extensions/KHR/EGL_KHR_fence_sync.txt

[2] http://www.khronos.org/registry/egl/extensions/ANDROID/EGL_ANDROID_native_fence_sync.txt

[3] http://www.khronos.org/registry/egl/extensions/KHR/EGL_KHR_reusable_sync.txt